History is Messy

In a single semester of a graduate level class, one learns a lot of information- some completely new information, some old information that you now think about differently, and some that you don’t understand right away. I found this to be true pretty quickly in my first semester as a public history masters student taking the “Introduction to Public History” class with Dr. Nieves last fall. Each week, my concept of the practice of public history, and even history itself changed and adapted the more we all learned and shared ideas together. Looking back on it now, it is interesting, when you are learning so much at a pace at which you have never learned before, what really sticks with you a year later. Of course, if Dr. Nieves asks, I remember much more than just this one thing, but truthfully, there is one lesson I learned throughout the course of last year that looms larger than the rest.

That one lesson is simply this: history is messy. Public history is (or at least should be) even messier. The messier the better, because as a public historian we deal with memory- how the past is remembered and how it is forgotten. This is complicated, but that is okay. Even more than being okay, it is the very reason why public history matters. We have a responsibility to share the messiness with the public, carefully considering the way this is done and the effects it will have. It may make us and our audience uncomfortable, but it will also make us all think, reflect and maybe even grow. At least that’s the goal.

When I began working with Dr. Nieves and Cassie Tanks on the Apartheid Heritages project this summer, I fully expected to work with difficult history (not just because the work is with the illustrious advocate for messy history himself, but also because the history being recorded in the Apartheid Heritages project is without a question a messy one.) As my primary focus for the summer would be metadata completion, however, I assumed there would be a bit less messiness. How could inputting information about an object- the date, a brief description of the artifact, the geographic place, and its latitude and longitude- be all that messy? It seemed pretty straightforward to me.

I was wrong- it got messy.

MA. 003: Zulu-Lulu Swizzle Sticks

One of the earlier objects I collected information about was this package of 6 novelty drink stirrers from the 1960’s. Each stirrer depicts a racist caricature of an African woman at a different age. The offensive “Zulu-Lulu” drink sticks refer to the Zulu people, the single largest ethnic group in South Africa who made up a substantial portion of South Africa’s urban workforce throughout the 20th century. The object in itself clearly is reflective of the complicated (messy) history of apartheid era South Africa, the racist portrayal highlighting the toxic spread of racist ideology in and outside of South Africa. In my first attempt at this item’s description, I basically said exactly that.

After a conversation with Dr. Nieves about this object, though, I found that the historical context could be complicated further. Even more than that though, this complication could come through in the metadata. I was instructed to think of the non-obvious, and incorporate that into the object’s description. With this logic, the description became focused not just on the content of the stir sticks themselves, but on what they could allude to as well. Given that the stir sticks are tied to alcohol, I added to the description an explanation of the apartheid state’s use of alcohol as a form of social control. Beer Halls, built in townships by the municipality, were seen as a method used by the apartheid government to make black people apathetic. During the June 16, 1976 uprising in Soweto, people could be heard shouting “less liquor, better education,” referencing the government’s creation of the beerhalls but lack of attention to opportunities like education. In this way, the object and its metadata reflect the complexities of this history, and just how messy it was.

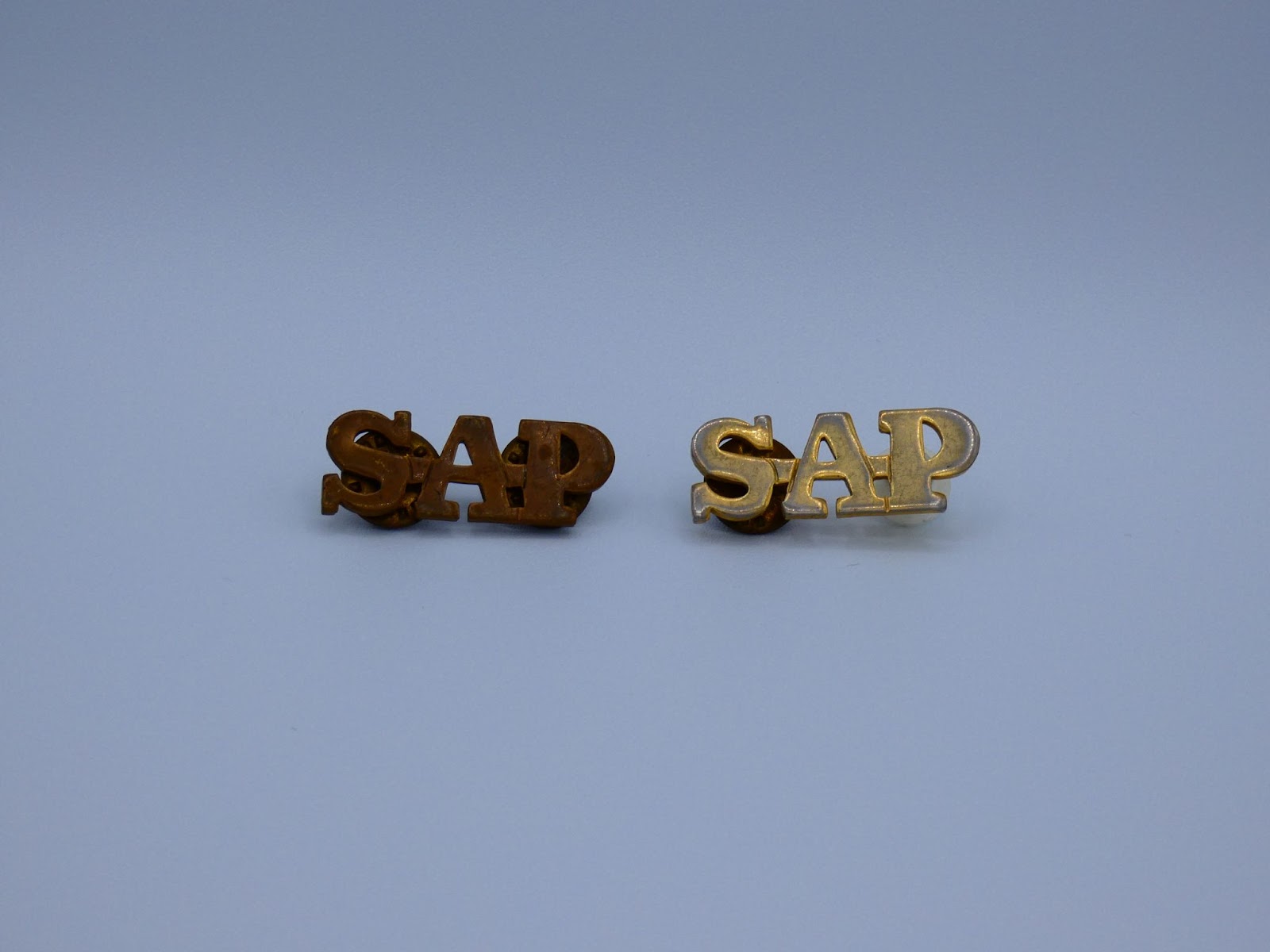

MA.002: SAP Shoulder Pins

Another moment of mind-opening metadata work that occurred for me this summer was in researching this pair of shoulder title insignias for the South African Police (SAP). We know that the SAP used violence, terror, and torture tactics to oppress the Black South African population during apartheid.

When fully worked through, this complicated relationship could be highlighted in the metadata description, as I learned with the swizzle sticks. When thinking about metadata fields, I find the description to be the most obvious place for metadata to get complicated, as it provides space for writing. Could the metadata get complicated anywhere else, though? Get even more messy?

Messiness of Coordinates

Both Cassie and Dr. Nieves showed me that even through something as simple as a latitude and longitude we could complicate the history and make sure its messiness was coming through. When tagging the geographic location for the set of SAP pins, a lot of places could factually make sense. South Africa would be an accurate tagging. Pretoria, where many SAP recruits were trained and the SAP headquarters is located today, could also be an accurate tagging. By tagging the pins at the latitude and longitude of John Vorster Square in Johannesburg, however, an important layer of complexity is added to the artifact. John Vorster Square was the largest and most notorious of the SAP stations, and was the primary location for SAP torture tactics. There, the SAP pins, and entire SAP uniform, is the most reminiscent of the brutality that allowed the National Party to maintain control over the black South African population in the name of “law and order.”

This history is messy and it needs to be told. Through metadata, I am finding, a public historian can do this work in ways that I did not expect. I feel privileged to work on the Apartheid Heritages project, a project that takes all of the information that I have learned about how to be a public historian, and puts it to practice. It shows me the potential of the field and the possibilities we have to complicate people’s understanding of the past and make a change with the work we do.

You must be logged in to post a comment.